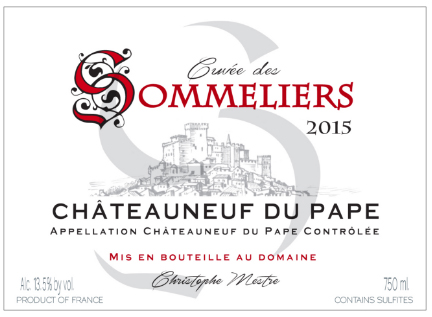

Classic. We’ve often written about the value of Gigondas. Located 20 minutes east of Châteauneuf-du-Pape, Gigondas produces wines of a similar intensity as its more famous neighbor, but usually at far more affordable prices. Our longtime source in Gigondas is the Domaine les Goubert, cited as a reference point in the region by Jancis Robinson and Robert Parker.

Goubert makes a delicious classic Gigondas, but today we’re offering Goubert’s flagship wine — the Gigondas Cuvée Florence — which more resembles a Châteauneuf-du-Pape than a Gigondas. Named for the family’s daughter Florence (now 30 and heading up the winemaking), this is a rich and age worthy wine that we have enjoyed for decades.

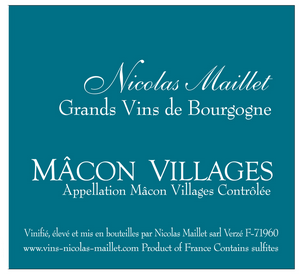

Exceptional. Cuvée Florence is a blend of grenache and syrah, raised in small Burgundy-style oak barrels. We have been buying this wine for more than 20 years, and can’t remember a better vintage than 2010. The nose is brooding and pretty, showing toasted black fruits, lavender, and chocolate. The mouthfeel is rich and silky, with plums, raspberry, and tobacco.

Josh Raynolds of Vinous awarded this wine 93 points, calling it “pure and impressively focused,” with “excellent clarity and lingering florality.” This wine ages beautifully, and we’ve enjoyed bottles of past vintages well into their second decade; but it’s a delight to drink today. Cellar it if you have the space and the patience; decant it if you don’t.

________________________

GOUBERT Gigondas “Florence” 2010

Ansonia Retail: $50

quarter-case: $42/bot

_

AVAILABLE IN 3- 6- AND 12- BOTTLE LOTS

_

or call Tom: (617) 249-3657

_

_

_____________________________

Sign up to receive these posts in your inbox:

_

_____________________________

_____________________________

Terms of sale. Ansonia Wines MA sells wine to individual consumers who are 21 or more years of age, for personal consumption and not for resale. All sales are completed and title passes to purchasers in Massachusetts. Ansonia Wines MA arranges for shipping on behalf of its customers upon request and where applicable laws permit.